The Master Musicians of Joujouka were sad to learn of the death of Blanca Hamri. Blanca died on 9 March 2023.

Blanca Hamri was introduced to the Master Musicians of Joujouka by Mohamed Hamri.

Blanca came to Morocco in 1972 and soon after her arrival met her future husband Mohamed Hamri. Mohamed was originally from Joujouka and took Blanca to the village on their first meeting.

Enchanted by the experience, she never left Morocco, living in Tangier and maintained a strong relationship with Joujouka, including visits to the annual festival in the village.

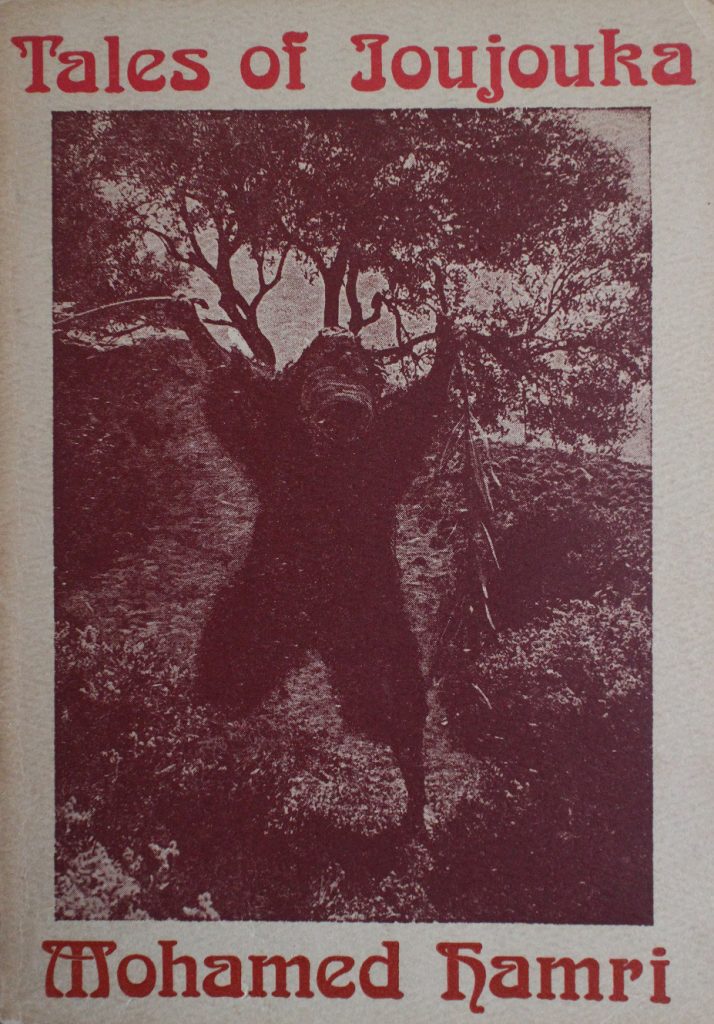

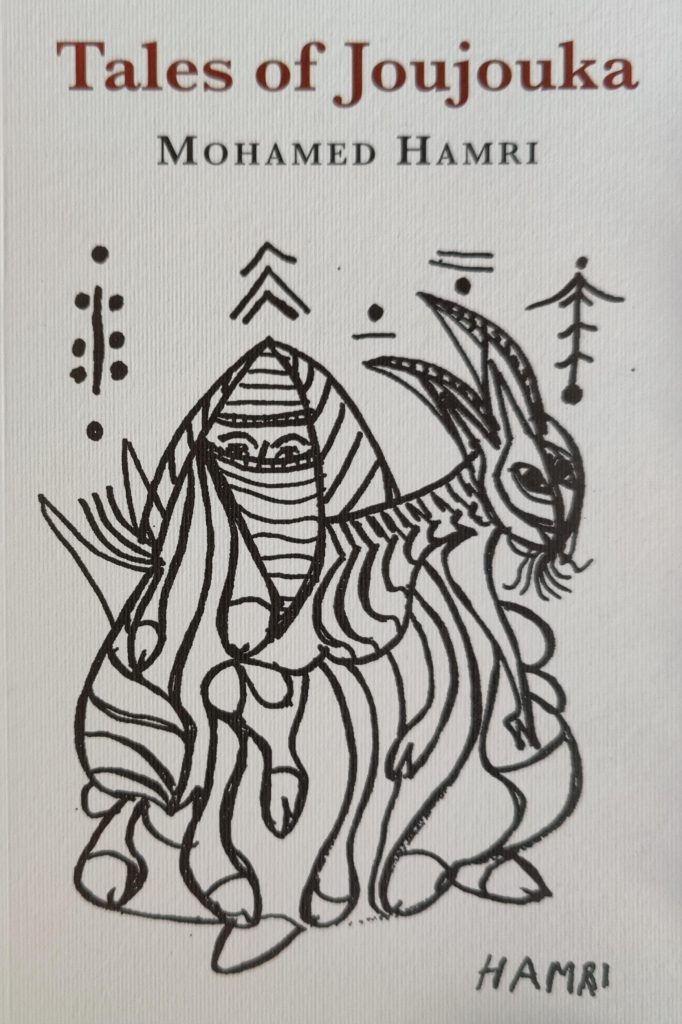

Together with her husband, Blanca wrote the Tales of Joujouka collection of short stories, originally published in 1975.

Blanca’s death was announced in a statement by the Tangier American Legation, who recently held an exhibition of Hamri’s paintings from Blanca’s collection: “Today we mourn the passing of the legendary Blanca Hamri, proud mother and grandmother, mentor to generations of students during her decades at the American School of Tangier, faithful steward of her husband Mohammed Hamri’s artistic legacy, loyal friend to the Legation and so many others, lover of life, and world-class raconteur. We will miss you greatly, Blanca.”

Frank Rynne, manager of the Master Musicians of Joujouka, said: “We worked on many adventures together and with Hamri. She was a remarkable woman and presence. May she rest in peace. I extend my deep condolences to her family and friends.”

Rikki Stein, who was in Joujouka when Blanca first visited the village at the time Ornette Coleman was recording in the village and continues to work with the Master Musicians, said: “So sorry to hear this. She was a remarkable woman. My sincere condolences.”

Blanca featured in a recent documentary produced by NHK in Japan and broadcast earlier this year talking about her experiences with the Master Musicians of Joujouka.

In a 2014 feature for the New York Times, Blanca said: “I stopped in Morocco by accident and I fell in love with the place as soon as I arrived. I remember seeing these men in long robes sitting on beautiful horses, and I thought, Jeez, if the army looks like this! The light was beautiful and you’d find people standing by the road holding up flowers and raspberries.

“Hamri was preparing for a festival with Ornette Coleman and he asked if I’d like to stay and so I did. I stayed in the blue hills. We were very nice together.”

These experiences inspired the collaborative work Tales of Joujouka, originally published in 1975 by Capra Press in California. It was translated from Darija by Blanca, featuring Hamri’s stories and folk tales from his home village Joujouka, including the history of the music performed by the Master Musicians of Joujouka and the legend of Boujeloud.

Blanca is survived by her daughter Sanaa Hamri and granddaughter Laila Hamri Fletcher.

The Master Musicians of Joujouka send our sincere condolences to her family at this time.

“The rhaita wipes the brain clean” – an interview with Blanca Hamri

Tales of Joujouka co-author Blanca Hamri interviewed in October 2022 by Richie Troughton.

“The rhaita wipes the brain clean. Because the sound is so powerful. And it does hit the brain in a very peculiar way, an interesting way. It is sort of a relative of a bagpipe.”

Blanca Hamri is talking about how her late husband Mohamed Hamri described the effect the distinctive instrument played by the Master Musicians of Joujouka can have on the listener.

Described by others as a “psychic cleanse” the instrument, and many unfolding patterns of interlocking harmolodic interplay when performed by a group en masse goes some way to explaining why, for hundreds of years, people have turned to this music to aid healing in issues of mental health affecting their loved ones.

This is some way from the introduction many from further afield have experienced the music, first heard outside of Morocco thanks to the recordings made in the village by Brian Jones, The Rolling Stones’ guitarist who visited in the late 1960s during a period away from his bandmates and subsequently released as the album Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka, with Jones’ own heavily phased and psychedelic remix of the original sounds he caught on tape.

The album featured a painting of Jones surrounded by a group of Musicians by Hamri, who was known as ‘The Painter of Morocco’. Incredibly, Blanca confessed to not owning a copy of the LP, released on The Rolling Stones’ own label imprint in 1971 after Jones’ death.

Hamri was from the village of Joujouka and by the 1950s was living in Tangier, where he met a cast of influential characters who, in turn, he introduced to the music. Among these was Brion Gysin, who professed to listen to their music every day, and with whom the pair ran the 1001 Nights restaurant, where groups of Musicians would take shifts holding a residency to perform nightly for guests.

The conversation with Blanca takes place at her home in the Kasbah, an unassuming apartment, located down a narrow side street, and from the outside offering no clue as to the grandeur within. The main living area boasts a fine collection of original Hamri artworks and a rooftop terrace offers panoramic views across the sprawling city, that has changed so much in the time Blanca has lived there, with heavy development ongoing, particularly around the ports that have taken over much of the once long sandy beachfront looking out to the Spanish coast.

“It would be easier all on one level,” said Blanca, aged 90 at the time of the interview. “But I don’t care. I like my house. Not easy to get to though.”

We have met to discuss the collection of short stories Tales of Joujouka, that Blanca is credited with translating from Hamri’s own telling of folk tales and mythology connected with Joujouka and the Master Musicians.

The stories were originally published in a 1975 edition by Capra Press, and have recently been republished in a new Éditions Jardin Marjorelle. The book was released to coincide with an exhibition of Hamri’s work at the Tangier American Legation, to run in Spring 2020, however, the initial run of dates was curtailed due to lockdown measures introduced in Morocco, as elsewhere around the world, due to the coronavirus. As things gradually started to reopen, so finally there was a chance for people to see the works of Hamri and read these, previously scarce, stories in a revised edition, that includes a couple of stories not featured in the original chapbook.

Morocco and Tangier have a rich history of storytellers, that no doubt cast an influence on visiting writers of the Beat Generation who soon found themselves charmed by the spell of the place and its people. This tradition continues in the Tales of Joujouka – where moral messages and comedic scenarios provide a clue as to the culture around which their folklore is based, such as the legend of Boujeloud, a half man, half goat figure, said to bring fertility to the villagers.

“There is a cave in Joujouka,” said Blanca. “I was always afraid to go into it. It is where Boujeloud showed Attar the secret of the flute. Well, years ago I could climb. Now, if I can get out of my chair I congratulate myself.”

But we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves. How did Blanca find herself in Morocco in the first place?

“Well, I came here because I went travelling,” said Blanca. “I had gone to California, Marin County, because many years before I had lived in San Francisco, and rather liked it, but I was starting my life anew. I had been in New York and everything, I don’t know what. And I decided to go to Marin. I knew somebody there. And I was there, it was nice, but I just, it wasn’t my cup of tea and everybody was blonde, so it was like … blonde and beards.

“If you don’t mind. Anyway, I found it quite boring, so I decided to go travelling and a friend went with me. The daughter of a friend of mine. And everywhere we went I didn’t like it. We went through Mexico, didn’t like it. Because I like to get the mood on the street. It’s easy to go to any place with a letter of introduction. You could be going anywhere. I mean, I like the street. I wanna know the street mood. I didn’t like anything. Even went to Guatemala, Belize, Athens, completely crazy. And on my way back, finally, I was done. She was going to go to Hawaii and go body surfing and I was going back to New York to start everything anew.

“In Athens we saw a very cheap flight to Morocco. I said, ‘Oh, I know somebody who…’ She said, ‘Well, on our way back why don’t we stop off?’. Fell in love immediately, with the country, and I never left. That’s how I came to Morocco, by accident. This was, 1972.

“Totally by accident. Because I hated every place I went to.”

She added: “It was a funny time. In Athens, the colonels were in charge. You’d sit at Syntagma Square, having coffee, and a tank rolls by. I was there, waiting to go back to New York.”

Blanca described her look at this time as “sort of crazy” that could cause some issues at customs.

It was not long into her stay in Tangier that she made acquaintance with an intriguing figure who would soon become her lover.

“We had driven in, with this friend of mine, and she pulled up to a light and someone came up to the car and they were chit chatty and she drove away. It was somebody. He looked very interesting. And I was surprised that she didn’t introduce me, ‘cause we were there for a few minutes. And I said, ‘How come you didn’t introduce me? He looked very interesting’. She said, ‘Well, he is very interesting, but forget it’. I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘Well, he’s a very good painter. But, he’s got a Czechoslovakian girlfriend, who’s 10 feet tall and I don’t know what, but he’s bad news when it comes to women’. So, he’s like the red flag in front of the bull.

“Anyway, three days later I’m at the Café De Paris, having my coffee and he comes by and says, ‘Oh, I think I saw you with Catherine, and blah blah blah. How are you? My name is Hamri. I am the ‘Painter of Morocco’’. I said, ‘How do you do?’ And he made me laugh. He had me in fits of hysterics. For an hour. Just sitting at the café. Comments he was making. Very funny. And he said, ‘I’ll take you to lunch’. I said, ‘Fine, thank you’. He said, ‘I’ll pick you up tomorrow at 11.30’. I was in the hotel, whatever it was called, and I thought, gosh, that’s early. Well, maybe it’s outside of town? Well, I get into the car, and then I found out afterwards, no one ever got in a car with Hamri, because he drove while talking to you.

“He never looked at the road. But he never had an accident. It was like everything went into stall, when he got behind the wheel. They all just sort of made an open canyon for him to go through (laughs). And anyway, we are in the car, we go to Asilah. We stop at the Hotel Hesperides. It’s all like very ancient Roman, Greek, and very crazy, and we keep driving, and we went to Larache.”

It turned out Hamri was taking Blanca to his home village in the Ahl Serif mountains.

“We finally got to Joujouka and the road was terrible. We bounced up the road. Then the Musicians played and I didn’t leave. He said, ‘I have to go back to Tangier because I am having a festival here in two days, but, you are welcome to stay here if you like’. Then the sheep go out in the morning and it was just beautiful. So I stayed. And I guess I never left. In three days I immediately was like, yes.

“And I wasn’t a young chicken when I came here. I was 40. Celebrating my 40th birthday, which is a seminal time, at that time, for women. You know, it’s like the first part of your life is done. Everyone always speaks to me as if I hadn’t lived before. You know (laughs) I had a whole life before.

“And then I had another whole life. And then I had my wonderful daughter. At an advanced age, which was wonderful.”

As Blanca’s housemaid serves us coffee, we begin to discuss how Tales of Joujouka came to be.

“With Tales of Joujouka, do you know how those stories got written? I mean, I wrote, adapted, how I would explain it? Hamri could not read or write. And his English, we never corrected him, because he was very to the point and comical. We loved it, but anyway, mea culpa. But, without him, the stories could not have been written.

“I would be sitting up there, always Musicians around, drinking tea and playing and they would burst out laughing. And I would say, ‘What are they laughing about?’ ‘Oh, it’s Titi, they say that he farts on his kif plants to make them stronger’. Well, that was the story. I made a whole story out of that one line.

“Oh, Fatima is too friendly with her goats? That was a story. So how do we say, I couldn’t have written it. What would I know about Fatima and her goats? You see? So I wrote. Adapted. That’s the only word. What else could I write? I couldn’t have written the stories without him. He could never have written the stories, without me.”

Or as Blanca puts it perhaps more succinctly in her introduction to the new collection, “The stories seemed to come into the room and lean over my shoulder.”

Though of course being in Joujouka and surrounded by the rural way of life in the village and music was an additional inspiration.

“I would be up there at night. There was no electricity. Candlelight. And I was writing the stories up there by hand. I was just writing for something to do and I liked it and I was very charmed and I always liked writing.

“And I’m a blabbermouth. So, I like to go into the details of everything and also (clears throat) my viewpoint amuses me many times. But that’s how the stories got written.

“Then somebody got in touch with Capra Press because he liked the stories got them published.

“And all of the illustrations for each story, they were Hamri’s drawings. They were very nice.

“There were two stories about Tangier, which were about things that did happen. The rat in the refrigerator.

“And the man who kept being bugged by someone selling my sister’s garlic, my wife’s onions, or something or other.

“They were all based on true things.

“And that’s how they got written.

“It’s just one liners. The story just created itself.

“But I never could’ve figured that out at all, it really opened the door for me.

“I really should start writing. It’s just that I can’t see. But! I can always talk into something. I’ve just been too busy, or too lazy, or too I don’t know what. Anyway. The beat goes on, that’s all I can tell you.”

Of the original publication Blanca said: “I got 50 copies, which have disappeared (laughs). But that’s okay. I’m proud of those stories, because I like those stories. It showed a group of people, at a certain time.”

Blanca described the scene of when the Master Musicians would play in the village and the impact of the music: “Oh, there were many. They would all meet in the town square, when they do Boujeloud. Many times they would play and somebody from another village would hear the music and come. Some stranger, and start dancing. Because it is very hypnotic, the music, when it goes up. Because they do this circular breathing. It sounds like one unearthly breath was taken and never completely expelled. As soon as you think it’s expelled, it’s come again, but it just goes on and on and on.

“The saxophone also has that. You hear it physically. But in that time, Charlie Parker was more, what they used to call bebop, which I hate. I always said bebop walks you somewhere and then somehow they lost their way and there they are wandering, and who needs it (laughs). And that didn’t last very long. But I did like jazz, I mean I grew up on jazz.”

One of the stories re-told in Tales of Joujouka is ‘The Legend of Boujeloud’ – a mythic folklore from the village.

“It affects you physically too,” Blanca said of the music. “Aisha Kandisha was somebody we talked about. The crazy woman that they brought out to dance to entertain Boujeloud, so that he would go back to his cave because he was so angry about them stealing his flute and not giving him the bride that they promised. That’s the whole scene with Aisha Kandisha.

“We used to have dancing boys (play the role of Aisha), but, you know, that’s the only way that they learn the music. There was no school to go to. You had to be a dancing boy in order to become a musician. That’s the only way they could learn, really learn the music.

“They would be directed, the boys would be directed with the musicians, with their eyes.”

On the future of the music from the village, Blanca highlighted the importance of young people continuing the musical traditions of Joujouka.

“They are not supported properly by the culture, which they should,” said Blanca. “The young people, they don’t want that, to dance for, like begging. You know, they should be revered. It’s like part of the culture. It’s part of their treasure.

“I remember during the time I was there, the culture didn’t (appreciate them), they were ashamed of it, in the beginning. Then it changed, as younger people came into those posts. And they started treasuring what belonged to them, because foreigners made such a fuss.

“The Rolling Stones came here, Brian Jones. The first time I went to Joujouka they were playing, the musicians were playing, sitting there listening to them, and then they started singing, and there was a picture of somebody, foreign, I didn’t know who it was, hanging on the wall. And they were singing, ‘Ohh, Brian Jones, in Joujouka, very stoned,’ and I nearly fell off my chair.

“What? And then I looked and it was a picture of Brian Jones. He liked them very, very much. He supported them. He really liked their music.”

Jones’ influence was immortalised in a song written by Mohamed Hamri, ‘Brian Jones Joujouka Vey Stoned’, that the Master Musicians of Joujouka play to this day.

“Yeah, it was a song,” Blanca said. “He wrote, ‘Nes mezyen’ – that is very, very nice, and then musicians sang that, ‘Oh, Brian Jones, in Joujouka very stoned’. Which I thought was hysterical, honestly.”

Continuing her description of the power of the rhaita, Blanca added: “It goes through you. I always wanted to have personal piper, to pipe me when I get home (laughs). Or a rhaita. Well, that’s just too strong.”

Joujouka 23 festival takes place 2-4 June. Last remaining tickets available and more information here

The Master Musicians perform two exclusive concerts in London at The Forge, Camden on 20th and 21st June. More information here